The French lawyer and epicurean Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin famously wrote, “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.”

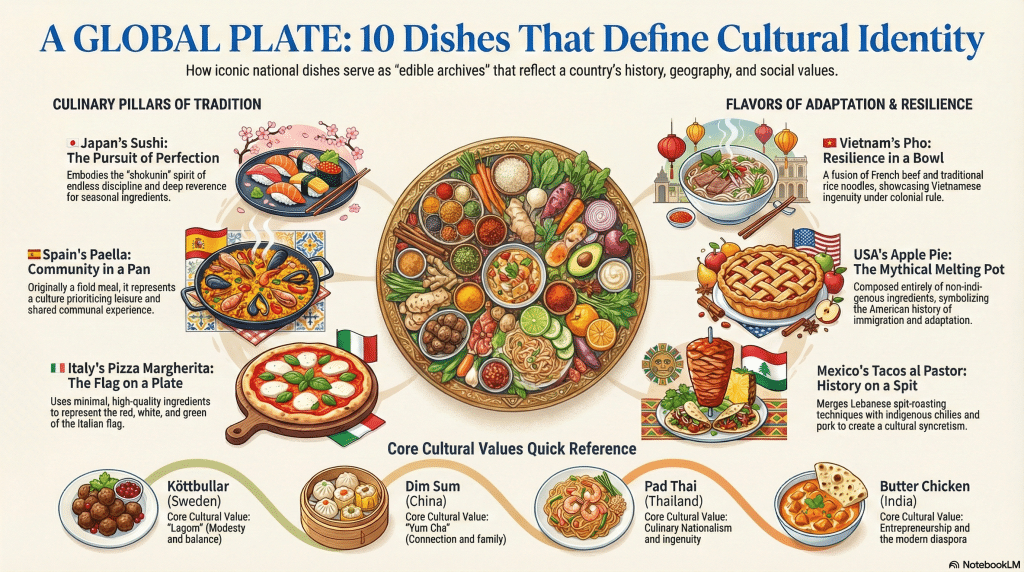

Food is perhaps the most accessible, tangible, and deeply sensory gateway into a culture. It is far more than mere sustenance; it is an edible archive of history. A single dish can tell the story of ancient trade routes, colonial occupations, geographical landscapes, religious beliefs, and the daily rhythms of a people’s lives. When we sit down to a meal in a foreign land, we aren’t just consuming calories; we are consuming identity.

Table of Contents

- Flavors of the World: 10 Iconic Dishes That Represent a Country’s Culture

- 1. Japan: Sushi (The Pursuit of Perfection)

- 2. Spain: Paella (Community in a Pan)

- 3. Vietnam: Pho (Resilience in a Bowl)

- 4. Sweden: Köttbullar (Comfort from the North)

- 5. China (Guangdong/Hong Kong): Dim Sum (The Tradition of Connection)

- 6. Thailand: Pad Thai (National Identity on a Noodle)

- 7. USA: Apple Pie (The Mythical Melting Pot)

- 8. Italy: Pizza Margherita (The Flag on a Plate)

- 9. Mexico: Tacos al Pastor (History on a Spit)

- 10. India: Butter Chicken (Murgh Makhani) (The Modern Diaspora)

- Deep Dive Podcast

- Related Questions

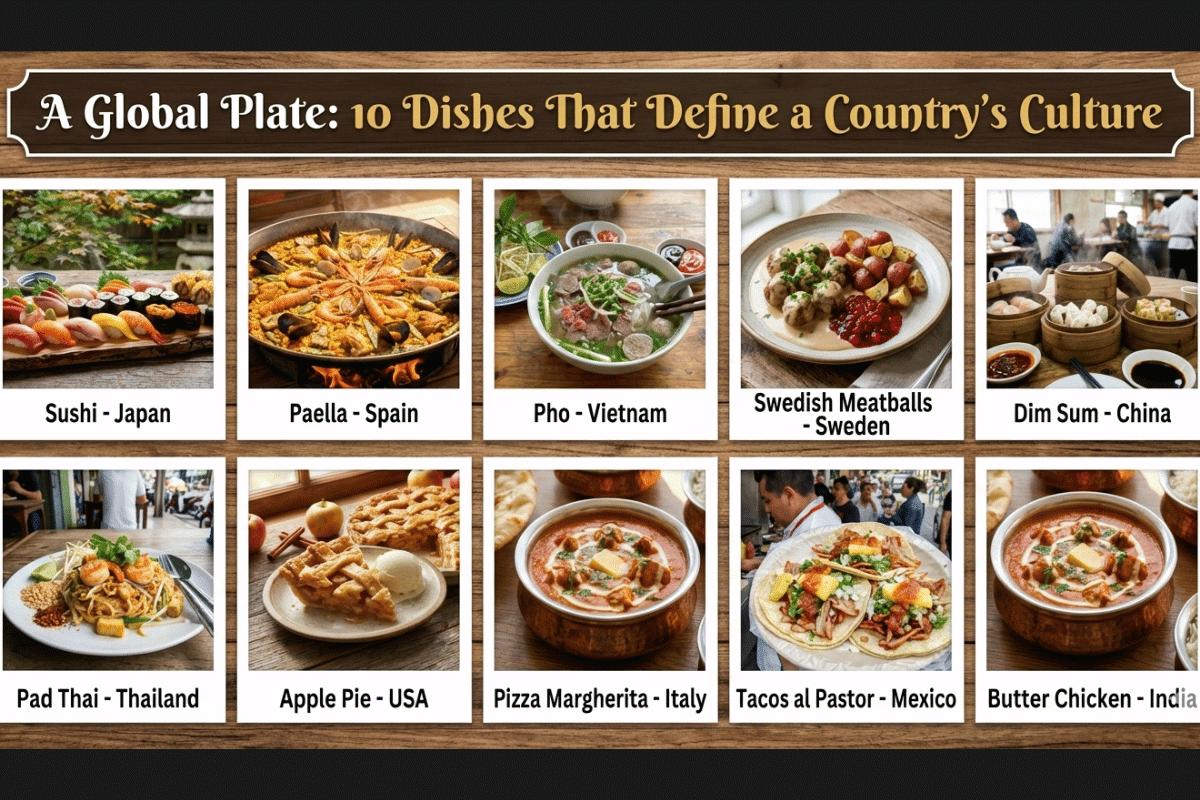

Flavors of the World: 10 Iconic Dishes That Represent a Country’s Culture

To understand a nation, you must taste it. You must understand why chili heat dominates in one region while creamy dairy soothes in another. You must see how scarcity bred ingenuity, turning humble scraps into national treasures.

In this culinary tour, we explore ten iconic dishes from around the world. These aren’t just popular foods; they are cultural touchstones, plates that define the soul of their nations.

1. Japan: Sushi (The Pursuit of Perfection)

Few cuisines on earth are as obsessively detailed as Japan’s, and nothing embodies this ethos quite like sushi. At its most basic, sushi is deceptively simple: vinegared rice (shari) combined with seafood (neta), usually raw. Yet, within this simplicity lies a universe of complexity that mirrors Japanese culture itself.

Sushi is a reflection of Japan’s island geography, a deep reverence for the gifts of the ocean, and a hyper-awareness of seasonality (shun). A master sushi chef performs a daily dialogue with nature, selecting fish that is at its peak at that exact moment of the year.

More deeply, sushi embodies the Japanese concept of shokunin—an artisan spirit dedicated to the endless pursuit of perfection through repetition. A chef may spend years doing nothing but washing rice before being allowed to handle fish.

The precise temperature of the rice, the angle of the knife cut, the exact pressure applied when forming the nigiri—every detail is scrutinized. In eating sushi, one tastes discipline, respect for ingredients, and a culture that finds profound beauty in minimalist restraint.

2. Spain: Paella (Community in a Pan)

If sushi is quiet introspection, Spain’s paella is a boisterous celebration. Originating in the Valencia region on the eastern coast of Spain, paella is not just a dish; it is an event.

Historically, paella was a midday meal for farmers and laborers cooked over open wood fires in the fields. They used the ingredients at hand: the short-grain rice grown in the watery Albufera lagoons, tomatoes, onions, snails, rabbit, and duck. Saffron, a legacy of Moorish rule in Spain, lent the dish its brilliant golden hue and distinct aroma.

Paella defines Spanish culture through its inherent sociability. It is cooked in a massive, shallow pan (paellera) designed to feed a crowd. It is meant to be eaten slowly, outdoors on a Sunday afternoon, surrounded by extended family and loud conversation. It represents a culture that prioritizes leisure, family connection, and the joy of shared experience. The most prized part—the socarrat, the crispy layer of toasted rice at the bottom of the pan—is fiercely fought over, a savory reward for communal patience.

3. Vietnam: Pho (Resilience in a Bowl)

Few dishes tell a story of historical adaptation and resilience as poignantly as Vietnamese Pho. This aromatic noodle soup, now beloved globally, is a relatively young dish, born in Northern Vietnam in the early 20th century during French colonial rule.

Before the French arrived, cows were valued in Vietnam primarily as draft animals, not food. The French, however, had a demand for steak. The Vietnamese butchers, left with an excess of beef bones and scraps, used their ingenuity.

They combined these discarded parts with their traditional rice noodles and indigenous spices like star anise, cinnamon, and roasted ginger. Some historians believe the word “pho” itself is a corruption of the French feu (fire), referencing the dish pot-au-feu.

Today, Pho is the heartbeat of Vietnam. It is eaten for breakfast on busy Hanoi sidewalks and late at night in Saigon alleys. It represents the Vietnamese ability to absorb foreign influences—Chinese noodles, French beef—and create something uniquely their own.

The crucial addition of fresh herbs, lime, and chili at the table allows each diner to customize their bowl, reflecting a culture that values balance, freshness, and individual agency amidst a collective history.

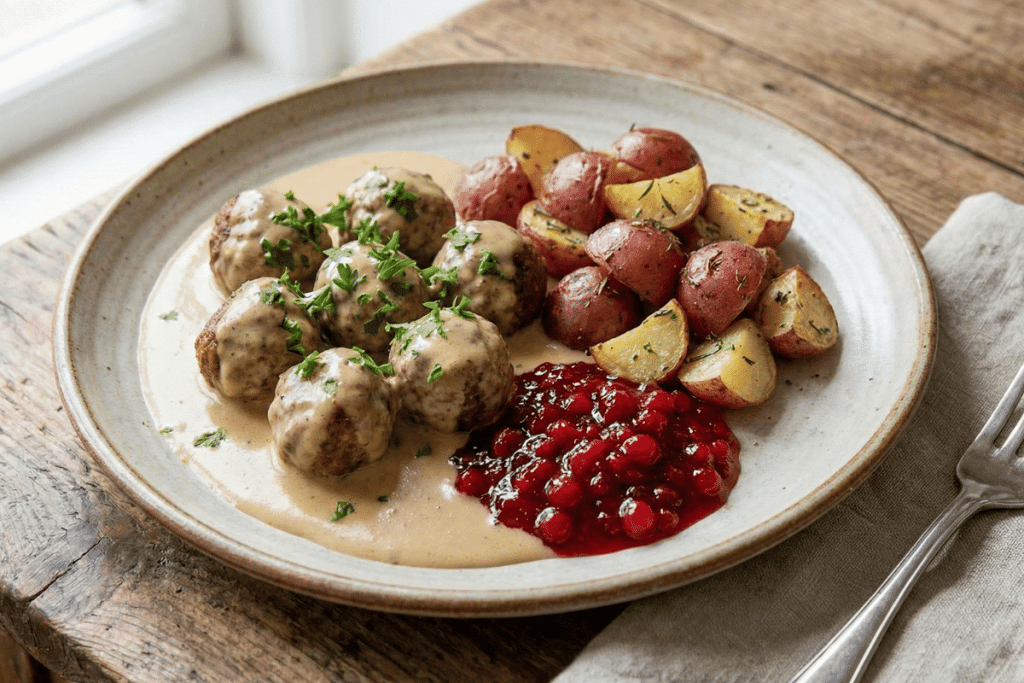

4. Sweden: Köttbullar (Comfort from the North)

Thanks to the global furniture giant IKEA, Swedish meatballs, or köttbullar, are perhaps the most recognizable Scandinavian export after ABBA. But beyond the cafeteria assembly line, these small, unassuming spheres of meat are deeply embedded in the Swedish psyche.

Traditionally a mix of pork and beef, bound with breadcrumbs and onion, gently spiced with allspice or white pepper, they are served with creamy gravy, boiled potatoes, and the essential sweet-and-sour lingonberry jam.

This plate perfectly summarizes the Swedish relationship with their environment. It is food meant to sustain people through long, dark, cold winters. The lingonberries speak to the Swedish tradition of allemansrätten (the right of public access), where foraging in the vast northern forests is a national pastime.

The dish represents comfort, practicality, and home. It embodies the Swedish concept of lagom—not too much, not too little, just right. Meatballs are humble, egalitarian, and deeply satisfying without being flashy, mirroring the Swedish cultural values of modesty and social equality.

5. China (Guangdong/Hong Kong): Dim Sum (The Tradition of Connection)

To talk about “Chinese food” as a monolith is impossible; the country’s culinary landscape is vast. However, the Cantonese tradition of Dim Sum, originating in Guangdong province and perfected in Hong Kong, offers a profound insight into Southern Chinese social culture.

Dim Sum, meaning “touch the heart,” is not merely a meal; it is an activity known as yum cha, or “drinking tea.” Historically, it began along the Silk Road as teahouses provided rest stops for weary travelers.

Over centuries, it evolved into a raucous, bustling culinary experience where diners choose small baskets of steamed dumplings, buns, rolls, and pastries from circulating carts.

Dim Sum defines the culture through noise and connection. A traditional Dim Sum hall in Hong Kong is chaotic, loud, and packed with multi-generational families shouting across large round tables. It is the ultimate expression of communal dining. It reflects a culture that places immense value on family structure and social networking.

The sheer variety of dishes—from delicate har gow (shrimp dumplings) to fluffy char siu bao (BBQ pork buns)—showcases a civilization with a deep, ancient appreciation for culinary artistry and varied textures.

6. Thailand: Pad Thai (National Identity on a Noodle)

Some national dishes evolve organically over centuries; others are consciously created. Thailand’s iconic Pad Thai falls into the latter category, making it a fascinating study in culinary nationalism.

In the late 1930s and 40s, Thailand (then Siam) was facing economic hardship and a rice shortage during World War II.

Prime Minister Plaek Phibunsongkhram wanted to modernize the country, forge a stronger sense of national identity, and reduce domestic rice consumption. He promoted noodle dishes, and his government standardized a recipe for stir-fried rice noodles that utilized cheap, local ingredients.

Pad Thai—rice noodles stir-fried with eggs, tofu, dried shrimp, garlic, chili, and peanuts, flavored with tamarind pulp, fish sauce, and palm sugar—became the blueprint for the nation’s palate. It brilliantly encapsulates the foundational pillars of Thai cuisine: the intricate balancing act of sweet, sour, salty, and spicy. It is a dish born of political necessity that became a beloved symbol of Thai ingenuity and vibrant, complex flavor.

7. USA: Apple Pie (The Mythical Melting Pot)

The phrase “As American as apple pie” is one of the great culinary ironies of the modern world. Why? Because almost nothing in a traditional apple pie is indigenous to the United States.

Apples originated in Central Asia. Wheat for the crust was first domesticated in the Middle East. Sugar cane came from Southeast Asia. Cinnamon and nutmeg are from archipelagos in the Indian Ocean. Even the concept of the encased pie was brought over by British, Dutch, and Swedish immigrants.

Yet, this is precisely why it defines American culture. The United States is a nation built on immigration, adaptation, and the mythologizing of domestic life.

As settlers moved across the continent, apples were easy to transport and grow (thanks, Johnny Appleseed), becoming a staple of the frontier diet. By the 20th century, the image of a cooling pie on a windowsill became shorthand for wholesome American values, nostalgia, and the comforting ideal of home.

It is a dish that proves a culture can adopt foreign elements so thoroughly that they become defining characteristics of the new homeland.

8. Italy: Pizza Margherita (The Flag on a Plate)

Italy is fiercely regional; a Tuscan will eat entirely differently from a Sicilian. Yet, one food has managed to unify the peninsula and conquer the globe: Pizza Napoletana.

While flatbreads with toppings have existed since antiquity, modern pizza was born in the poor, crowded streets of 18th-century Naples. It was cheap street food, eaten quickly by the working class.

The defining moment came in 1889, when, according to legend, Queen Margherita of Savoy visited Naples. To honor her, local pizzaiolo Raffaele Esposito created a pizza featuring the colors of the newly unified Italian flag: red (San Marzano tomatoes), white (mozzarella di bufala), and green (fresh basil).

The Pizza Margherita embodies the Italian culinary genius of “less is more.” It relies entirely on the quality of three or four humble ingredients. It reflects a culture passionately dedicated to regional agriculture, simplicity, and passion.

Today, the arte dei pizzaiuoli napoletani (the art of Neapolitan pizza making) is protected by UNESCO heritage status, proof that Italy views this dish not just as lunch, but as a national treasure representing their soul.

9. Mexico: Tacos al Pastor (History on a Spit)

The taco is the undisputed king of Mexican street food, a versatile canvas for infinite regional variations. But few tacos tell a more compelling historical story than Tacos al Pastor (Shepherd-style Tacos).

Walking through Mexico City at night, you will see glowing vertical spits of marinated pork, topped with a pineapple, rotating next to an open flame. If this looks suspiciously like Middle Eastern shawarma or Greek gyros, that’s because it is.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a wave of Lebanese immigrants arrived in Mexico. They brought their tradition of spit-roasting lamb.

Over time, Mexican culinary culture absorbed and adapted this technique. The lamb was replaced with pork (the favored meat of Mexico), marinated in indigenous chilies (guajillo, ancho) and spices like achiote.

The pita bread was replaced by the ancient corn tortilla. The pineapple on top adds enzymes that tenderize the meat and provides a burst of sweetness to counter the spicy pork.

Al Pastor is a delicious example of Mexico’s history as a “melting pot”—a vibrant syncretism of indigenous Aztec roots, Spanish colonial influence, and later immigrant waves, all wrapped in a tortilla.

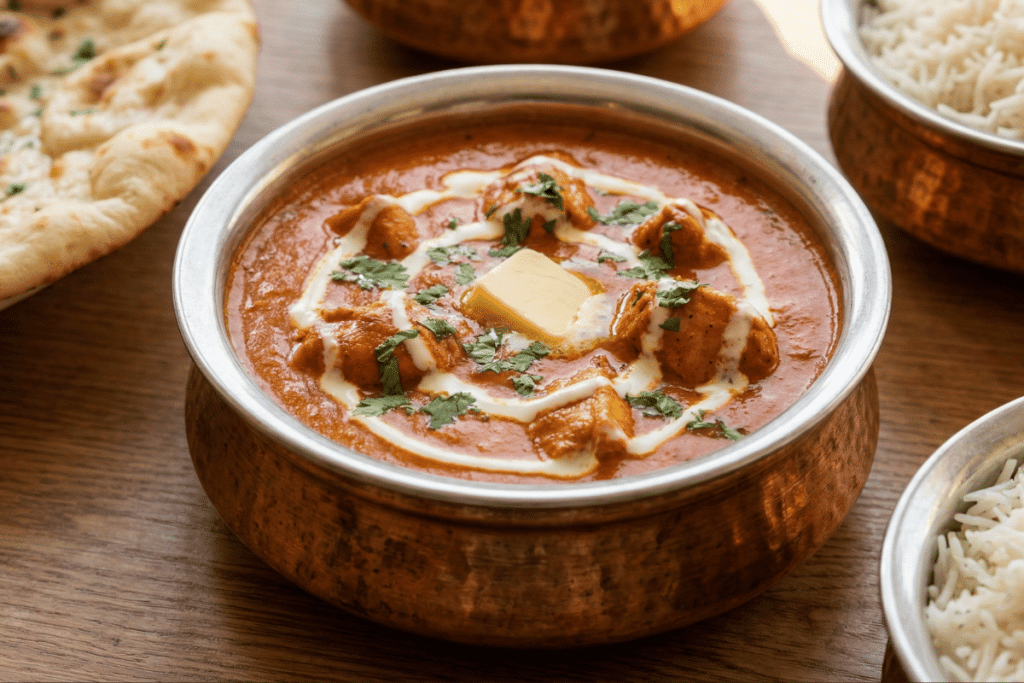

10. India: Butter Chicken (Murgh Makhani) (The Modern Diaspora)

Indian cuisine is incredibly diverse, a subcontinent of varied spices and techniques. Yet, the dish most recognized globally as “quintessential Indian” is a modern invention born amid political tragedy.

Following the Partition of India in 1947, refugees flooded into Delhi from what became Pakistan. Among them were Kundan Lal Gujral and Kundan Lal Jaggi, who opened a restaurant called Moti Mahal. They faced a practical problem: their tandoori chicken, cooked in clay ovens, would dry out if not sold immediately.

To save the leftover chicken, they simmered it in a rich sauce made of tomatoes, cream, butter, and mild spices.

Murgh Makhani (Butter Chicken) was born. It is opulent, mildly spiced, and comforting. It became the ambassador dish for Indian cuisine in the West because its creamy profile was accessible to palates unaccustomed to intense chili heat.

It defines modern Indian culture not by its ancient roots, but by its 20th-century diaspora—a story of entrepreneurship, adaptation, and the global spread of South Asian identity post-independence.

When we look at these ten dishes, we see more than ingredients on a plate. We see the entrepreneurial spirit of refugees in Delhi and the precision of artisans in Tokyo. We see the communal warmth of a Valencian field and the bustling energy of a Hong Kong teahouse.

Food is the great connector. In a world that often emphasizes our differences, sitting down to break bread—or scoop rice, or slurp noodles—remains a universally human act. To eat the food of another culture is to partake in a silent act of diplomacy, acknowledging a shared humanity that transcends borders.

So the next time you travel, or even just order takeout, remember: you aren’t just eating dinner. You are tasting history.

Deep Dive Podcast

Check out our Deep Dive Podcast

At A Bus On A Dusty Road, we talk about travel, life, and ex-pat living. We are all about “Living Life As A Global Citizen.” We explore social, cultural, and economic issues and travel.

We would love to have you be part of our community. Sign up for our newsletter to keep up-to-date by clicking here. If you have any questions, you can contact me, Anita, by clicking here.

Listen to our Podcast called Dusty Roads and Deep Dive By Dusty Roads Podcast. You can find it on all major podcast platforms. Try out listening to one of our podcasts by clicking here.

Subscribe to our A Bus On A Dusty Road YouTube Channel with great videos and information by clicking here.

Related Questions

The Vietnamese Bun Cha Food Dish, All You Need To Know

Bún Chả is a Vietnamese food dish that is thought to have originated in North Vietnam. It is made from rice noodles, grilled pork, salad, and a Bún Chả fish sauce mixture. It is a dish you can learn to make and serve in your home. Bún Chả became very famous when the U.S. President Barack Obama sat down with CNN’s Anthony Bourdain in a small local Bún Chả noodle shop in Hanoi, Vietnam.

Read our blog The Vietnamese Bun Cha Food Dish, All You Need To Know by clicking here.

Why is Rice Important to the Vietnamese?

Rice is essential to the Vietnamese because rice is one of the world’s most important staple foods. Due to its climate, Vietnam is one of the world’s leading rice producers. As with many things in Vietnam, there is folklore and legends about rice and rice production. You can visit many places in Vietnam to see some spectacular rice fields and rice terraces.

You can find out more about this by reading our blog, Why Rice is Important in Vietnam, What You Need To Know by clicking here.

What About Vietnam’s Morning Exercise?

The mornings in Vietnam are always extremely active, with people out and about exercising. It is usually safe to go out early in Hanoi, Vietnam. The streets are always bustling with a lot of activity and excitement. People in the city tend to start their days very early. You must also get up early to see the early morning exercise. There are a lot of places in Hanoi where you can see a lot of early-morning exercisers. Starting the day early is a habit that many people have throughout all Asia.

You can see a video about morning exercise in Vietnam and read our blog called Early Morning Exercise in Hanoi, Vietnam, What You Need to Know by clicking here.