The Great Depression is a historical behemoth—a testament to how intertwined economic policies, market dynamics, and international relations can merge into a perfect storm, derailing global prosperity. The economic policies preceding the Great Depression set the stage for this unparalleled economic catastrophe. Fueled by protectionist sentiments, measures like the Smoot-Hawley Tariff formed the opening chords to a symphony of economic dissonance.

Moreover, the Federal Reserve’s actions, or at times inaction, wielded significant influence over the nation’s financial well-being, leading to widespread repercussions. As we venture back to scrutinize the events leading up to and during the Stock Market Crash of 1929, the vital role of banks and financial institutions, and the convoluted web of international trade dynamics, we find a complex tapestry of causation that rendered the world’s economies inert.

Table of Contents

- Economic Policies Preceding the Great Depression

- Stock Market Crash of 1929

- Role of Banks and Financial Institutions

- The Contribution of Banking Practices to the Onset of the Great Depression

- Banking Expansion and the Illusion of Prosperity

- The Dichotomy of Urban and Rural Banking Challenges

- Credit and the Consumption Culture

- The Unsustainability of Golden Decade Growth

- The Cascading Effect of Bank Insolvency

- The Ripple Effect on the Economy

- Financial Institutions and the Deflationary Vortex

- International Trade and Global Responses

- The Interplay of Global Trade and Economic Descent during the Great Depression

- The Collapse of Global Trade Networks

- Debt, Reparations, and International Resentment

- The Gold Standard’s Rigid Grip

- Disintegration of Financial Symbiosis

- Economic Nationalism and Retraction

- The Rise of Autarky and Its Discontents

- Harbingers of Recovery and Reconnection

- Related Questions

Economic Policies Preceding the Great Depression

Economic Policies and Their Role in the Advent of the Great Depression

The Great Depression, a global economic downturn in 1929 and persisted well into the late 1930s, is a stark reminder of the delicacy inherent in economic structures. A multifaceted phenomenon, the Great Depression’s onset was precipitated by a plethora of factors, not least among them being the economic policies of the time.

The Emergence of Fiscal Frailty

Preceding the Great Depression, the United States economy flourished throughout the Roaring Twenties, an age marked by a surge in consumer spending and speculative investments. Yet, beneath the veneer of prosperity lay an economy riddled with weaknesses and vulnerabilities exacerbated by the economic policies of the time.

Federal Reserve Policies: Growth and Contraction

The Federal Reserve, the central banking system of the United States, played a pivotal role. Initially, in the early 1920s, the Federal Reserve adopted a policy promoting easy credit and low interest rates, intending to foster economic growth and assist Great Britain in returning to the gold standard at pre-war parity.

This policy underpinned expansive borrowing and leverage in stock market investments but failed to constrain excessive speculation and the growth of an asset bubble. Subsequently, when the Federal Reserve, aiming to curb these speculative excesses, raised interest rates in 1928 and again in 1929, the cost of borrowing increased markedly.

Businesses, consumers, and speculators strained under the weight of higher interest rates, precipitating a reduction in spending and investments that stoked the fires of a forthcoming recession.

Tariffs and International Trade

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, passed in 1930, aimed to protect American industries by imposing substantial tariffs on various imported goods. In theory, these tariffs were designed to stimulate domestic production and shield American workers from international competition. However, their practical effect was widely counterproductive; international trade partners retaliated with tariffs of their own, curtailing global trade and hastening the economic decline.

In a world increasingly connected by the intricate webs of commerce, this policy vitiated international markets, inadvertently stifling economic activity at home and abroad.

Fiscal Policy and Government Spending

Fiscal policy during the 1920s also contributed to the vulnerabilities that defined the period preceding the Great Depression. The federal government adhered to a doctrine of limited intervention, maintaining balanced budgets and low taxes. Though seemingly prudent, this stance offered little stimulus to a needy economy.

As the economy languished, the government failed to inject sufficient capital into the system or provide robust social safety nets for the unemployed and impoverished—an omission magnified the human suffering endured throughout the Depression.

The economics of the Great Depression are thus best understood through a prism of policy choices intricately woven into the fabric of the era’s economic tapestry. It was not merely a singular policy but a confluence of decisions and approaches, both active and passive, that catalyzed and exacerbated the economic cataclysm known as the Great Depression.

Reflecting on such a pivotal historical moment underscores an essential truth: when inappropriately calibrated, economic policies can precipitate profound consequences, unraveling the socioeconomic threads that underpin communities and nations.

Through the lens of history, the lessons derived from the Great Depression continue to inform modern economic policies, serving as a cautionary tale of restraint and insight into the stewards of economic systems.

Stock Market Crash of 1929

Speculative Bubbles and Market Psychology

The stock market crash of 1929 did not materialize out of thin air; instead, it was the culmination of a series of events, behaviors, and economic conditions that created an environment ripe for financial disaster. Among these dominos was the rampant speculation that permeated the 1920s, often called the ‘Roaring Twenties’ due to the era’s unbridled optimism and economic growth.

Speculative bubbles are a fascinating study of human psychology and market dynamics. They are characterized by assets being traded at prices significantly higher than their intrinsic values. During the 1920s, the American public was bewitched by the allure of the stock market, enticed by the promise of wealth and the perception that prices could only ascend.

A surge in individual investors marked this era of speculation. Many were inexperienced, and they employed margin buying, purchasing stocks with borrowed money in anticipation of making lucrative profits upon selling.

Contrary to prudent investment strategies grounded in fundamental analysis, many investments during this period were predicated on a belief in continued rapid growth. However, such optimism ignored the fundamental disequilibrium between the increasing stock prices and the actual value of the companies represented.

The widespread engagement in margin buying meant that the stability of individual fortunes and the financial system hinged precariously on the constant upswing of stock values.

The Risk of Leverage

When discussing the 1929 market crash and its historical implications, the role of leverage, specifically through margin buying, commands considerable focus. The prevailing ethos of leveraging investment to maximize potential returns amplified the eventual downfall, as high levels of borrowed capital magnified losses.

As stock prices plummeted, margin calls were issued en masse—investors were required to pay the balance they owed. With prices in freefall and overextended credit lines, many could not meet these calls, leading to forced sell-offs of assets at a loss. This drove prices down even further in what can be described as a feedback loop of financial calamity, underscoring the inherent fragility of an overly leveraged market.

Economic Domino Effects

The stock market’s collapse catalyzed a cascade of economic woes, embodying the financial sector’s interconnectivity with the broader economy. While the fiscal policy and government actions of the time certainly influenced the unfolding of events, the market collapse translated into an immediate loss of wealth for numerous Americans.

Banks, heavily invested in the stock market, faced insolvency as their holdings’ values disintegrated. The subsequent wave of bank failures manifested in a contraction of the money supply, leading to deflation and further diminishing the capacity of consumers to purchase goods and services—a dire consequence for a consumer-driven economy.

The pervasive climate of insecurity and mistrust engendered by the crash led to a tightening of credit and a reduction in spending, exacerbating the slump into a full-fledged depression.

Business investments stalled, prices for commodities and goods plunged, and companies began downsizing their workforce or closing entirely. This upsurge in unemployment created a cascading effect on income and spending, propelling the economy deeper into the throes of the Great Depression.

Long-term Effects on Financial Regulation

The dramatic crash of 1929 and the subsequent Great Depression left an indelible mark on finance and economic policy. They prompted a reevaluation of the regulations governing financial institutions and markets.

In the following years, significant legislative reforms, including the Banking Act of 1933 and the Glass-Steagall Act, instituted greater separation between commercial and investment banking to protect depositors’ funds.

The establishment of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 1934 was another pivotal outcome. It fundamentally reshapes the oversight of the stock market, and broker-dealers’ conduct to mitigate the potential for future speculation-driven bubbles and market collapses.

These reforms reflected a profound shift in the philosophy governing the financial markets—one aimed at increased scrutiny, oversight, and prudence to forestall the potential for economic turmoil on such a catastrophic scale.

In conclusion, the 1929 stock market crash’s significance in precipitating the Great Depression is multifaceted, highlighting the critical interplay between speculation, investor behavior, and economic policy.

The collapse was a stark reminder of the market’s susceptibility to collective euphoria and the reverberating consequences of its descent. The lessons from this period underpin financial regulatory practices today, standing as a testament to the importance of striking a balance between economic growth and systemic stability.

Role of Banks and Financial Institutions

The Contribution of Banking Practices to the Onset of the Great Depression

As the world analyzes the economic downturn that defined the Great Depression, the intricate role of banking institutions emerges with stark clarity. Banks, the lynchpins of financial stability at the time, were in the vortex of a storm that would weaken economies globally.

Banking Expansion and the Illusion of Prosperity

In the years before the Great Depression, banks vigorously expanded their operations. During this period, they witnessed an increase in the number of banks and a proliferation of larger institution branchings. Banks served as conduits for capital, facilitating investments and the growth of enterprises nationwide.

This aggressive expansion, however, was accompanied by a dubious practice: minimal regulation allowed banks to engage in speculative investments, tying the fortunes of everyday depositors to the stock market’s variable moods.

The Dichotomy of Urban and Rural Banking Challenges

Differing challenges beset banks depending on their geographic stronghold. Urban banks, with their vast networks, often became overextended, intertwining their fates indiscriminately with those of the stock market. On the other hand, rural banks faced pressures from declining crop prices and an agricultural sector heavily burdened by debt. This dichotomy led to a fragmented banking system – one prone to shock from either end of the spectrum.

Credit and the Consumption Culture

Credit was the lifeblood of economic expansion in the 1920s, feeding the consumption culture that defined the era. Banks extended credit liberally, encouraging individuals and businesses to engage in financial overreach. Such an environment incubated a false sense of wealth; the accessibility of credit masked the economic frailties that widespread indebtedness was sewing into the fabric of financial systems.

The Unsustainability of Golden Decade Growth

The “Golden Decade” saw unprecedented economic growth, yet the growth was unsustainable beneath the sheen. Banks played a pivotal role in abetting this unsustainable surge by distributing loans for stocks, real estate, and consumer goods. The lack of stringent lending criteria and oversight paved the way for an economic overextension that would breed catastrophic consequences.

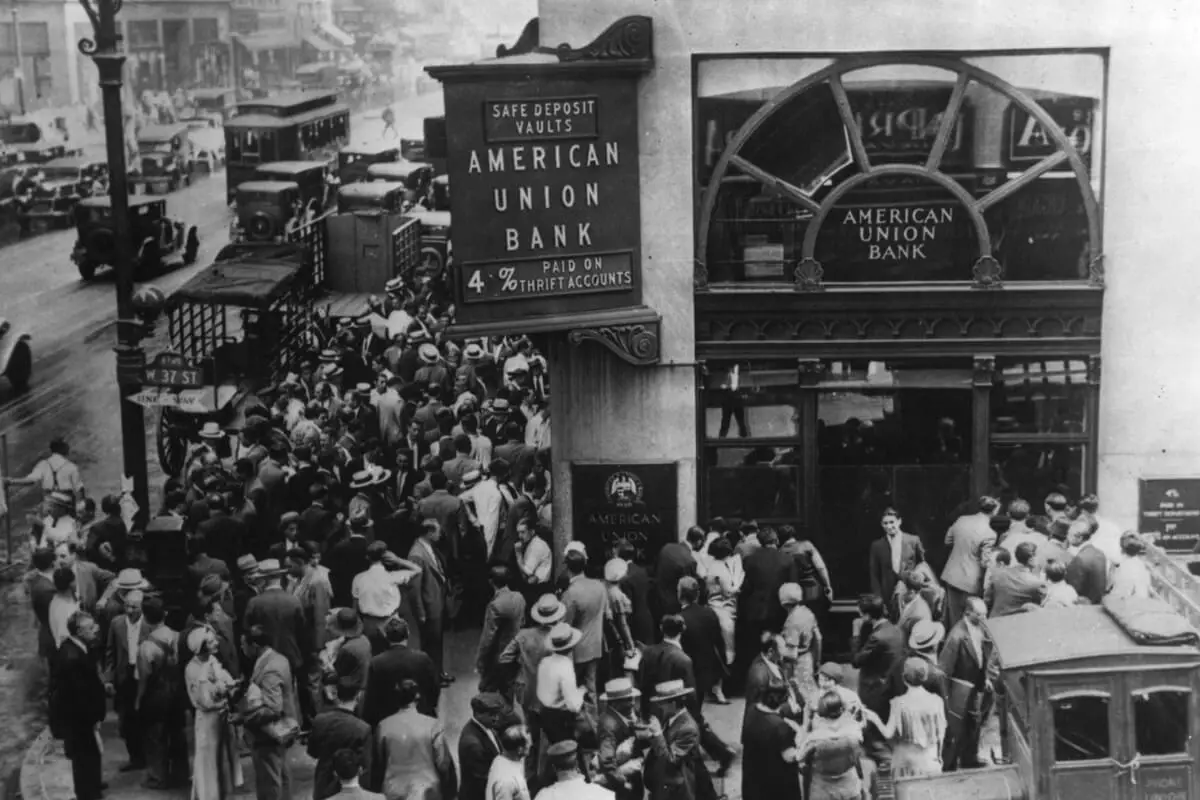

The Cascading Effect of Bank Insolvency

As the stock market crumpled like a paper tower, banks encountered a cascading effect of insolvency. The intimate relationship between banks and the stock market became their undoing. With a substantial portion of their assets tied up in plummeting stocks, banks faced margin calls they couldn’t meet, leading to runs on banks by desperate consumers and a subsequent collapse in banking confidence.

The Ripple Effect on the Economy

As banks floundered and collapsed, the ripples spread through the economy. Credit dried up swiftly, snatching away the fuel that had powered economic activity. Companies failed without access to loans, causing unemployment rates to surge. The chains of the financial system, once interlinked to facilitate growth, now propagated a regressive wave that sucked the economy into a downward spiral.

Financial Institutions and the Deflationary Vortex

The roiling economic seas churned up a deflationary vortex as banks, enfeebled by non-performing loans and asset devaluation, curtailed their lending activities. This constriction of credit aggravated deflationary pressures by reducing the money circulating in the economy.

International Trade and Global Responses

The Interplay of Global Trade and Economic Descent during the Great Depression

In the annals of economic history, the Great Depression is a testament to the intricate tapestry of international trade and diplomacy shaping national fortunes. At its core, the Depression was not merely an American saga but a global catastrophe, where the dynamics of international trade played a pivotal role in deepening economic woes worldwide.

The Collapse of Global Trade Networks

The late 1920s and early 1930s global trade landscape was a battleground of competing interests and protectionist policies as countries scrambled to shield their economies from external shocks.

The infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, envisioned to protect domestic industries by hiking duties on imported goods, inadvertently sparked a trade war, prompting retaliatory tariffs worldwide. This reciprocation constricted international trade as barriers rose and global trade volumes plummeted by approximately 50 percent from 1929 to 1934.

Debt, Reparations, and International Resentment

In the aftermath of World War I, European economies were shackled by reparations and debts, particularly those imposed on Germany. The intricate web of international debt payments hinged on German reparations payments facilitated by American loans.

The paralysis of international finance in the wake of the Great Depression undermined this delicate balance. As U.S. lenders retracted funds out of sheer necessity or panic, debtor nations found themselves bereft of the means to honor their financial obligations.

The Gold Standard’s Rigid Grip

A critical piece in the international economic puzzle was the Gold Standard, a system in which nations pegged their currencies to a fixed quantity of gold, ostensibly guaranteeing stability. However, adherence to this standard during the Depression imposed inflexibility in monetary policy.

As economies contracted, their inability to devalue currency to stimulate exports led to devastating deflation. Nations like the United Kingdom eventually abandoned the Gold Standard in 1931, opting for domestic economic stimulus over the rigidity of gold parity.

Disintegration of Financial Symbiosis

The intricate financial interdependence cultivated in the Roaring Twenties disintegrated under the stress of a faltering U.S. economy. Once the lubricant of commerce and reconstruction, international lending evaporated as American banks imploded under the weight of defaults and withdrawals.

Investment in foreign markets became an untenable gamble. The cessation of these financial flows left a vacuum in international finance that no other nation was prepared or willing to fill.

Economic Nationalism and Retraction

As countries grappled with dwindling trade, declining revenues, and soaring unemployment, a retreat into economic nationalism became the misguided prescription of the age. Governments prioritized domestic recovery at the expense of international cooperation, further exacerbating global economic rifts. These policies were not mere choices but perceived necessities in a climate where competitive devaluation and trade barriers were seen as the only lifeboats in a storm of economic despair.

The Rise of Autarky and Its Discontents

Some nations turned inwards, pursuing policies of autarky – self-sufficiency, independent of international trade. While partly reacting to precarious global trade conditions, autarky reflected broader ideological shifts towards authoritarianism and control. Yet, such an inward pivot could not effectively replace the prosperity once derived from expansive global trade networks, and thus, it served to elongate the economic malaise.

Harbingers of Recovery and Reconnection

The path to recovery was a slow rekindling of international trade and cooperation, signposted by events such as the 1934 Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act in the U.S., enabling tariff reductions through bilateral agreements. The reconstitution of trade ties and a gradual move away from protective barriers allowed for a resurgence of international commerce, albeit calibrated to the cautious optimism of nations emerging from deep economic scarring.

Reflecting on the nuances and complexities that international trade dynamics lent to the Great Depression, it becomes starkly apparent that economic interdependence is a double-edged sword. Potent in its ability to elevate yet equally capable of cascading failure, it underscores the perpetual quest for balanced and resilient global trade systems. While our contemporary world is not immune to echoes of the past, lessons from this era continue to inform and shape economic discourse and policy, lest the shadows of the 1930s darken future horizons unperturbed.

As the shadows of the Great Depression recede into history, the monumental scope of its impact remains a crucial study for understanding economic resilience and vulnerability.

The fusion of domestic and international factors that spiraled into the economic void of the 1930s calls for a careful reflection on the institutions that hold our financial systems together.

Confronting the failures and shortsightedness that led banks to crumble, governments to retreat into isolationism, and communities to suffer under widespread poverty illuminates the path to establishing a more secure economic future.

By examining the era’s interwoven causes and rampant devastation, we can distill lessons that transcend time, ensuring that the stark realities of the past inform a brighter, more stable economic horizon.

At A Bus On A Dusty Road, we talk about travel, life, and ex-pat living. We are all about “Living Life As A Global Citizen.” We explore social, cultural, and economic issues and travel.

We would love to have you be part of our community. Sign up for our newsletter to keep up-to-date by clicking here. If you have any questions, you can contact me, Anita, by clicking here.

Listen to our Podcast called Dusty Roads. You can find it on all major podcast platforms. Try out listening to one of our podcasts by clicking here.

Subscribe to our A Bus On A Dusty Road YouTube Channel with great videos and information by clicking here.

Related Questions

Is It True America Is Both Capitalist And Socialist?

America is considered both a capitalist and socialist economy; America is deemed to have a mixed economy which means it has both capitalist and socialist characteristics. Having a mixed economy in America is essential because there are some things that we need the government to intervene with on behalf of the public good.

By clicking here, you can discover Is It True America Is Both Capitalist And Socialist?.

What Makes Confederates Different From American Colonists?

The American colonist was primarily English, Dutch, and French settlers who arrived in the American colonies beginning in 1607. They were the individuals who fought for the independence of America in the American Revolution from Great Britain. On the other hand, the Confederates were part of the southern United States. In 1861, they fought against the northern states of the union in what is known as the American Civil War.

By clicking here, you can discover What Makes Confederates Different From American Colonists?

All About England’s Rivers Flowing Into The English Channel

Several major English rivers flow into the English Channel. These rivers include River Avon, River Dart, River Ouse, and The Solent. All of these flow into the English Channel, a body of water between England and the European mainland, especially France.

By clicking here, you can discover All About England’s Rivers Flowing Into The English Channel.